Walking Inside My Story

“You either walk inside your story and own it or you stand outside your story and hustle for your worthiness.”–Brene Brown

I’ll never forget the day I stood in the archives at the Z. Smith Reynolds Library at Wake Forest University when an historian friend of mine showed me the bill of sale from the two women that my ancestors enslaved. That was the moment my family narrative began unraveling for me.

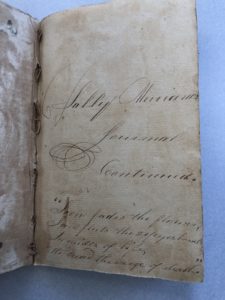

That day in Special Collections had started like most. I emailed the staff before I came, asking them to pull the nineteenth century letters I needed to read, scan, and transcribe for my thesis on my great-great-great-great grandmother, Sarah Merriam Wait. Sally, as she was known, was the wife of Wake Forest’s first president, and while Samuel Wait’s life had been examined by various historians, Sally’s voice was silent. I wanted to change that. I enrolled in graduate school to pursue a MA in Liberal Studies and dive into the hundreds of documents written in Sally’s and Samuel’s hand. It was tedious work and by the end, I had read nearly every document that survived, including Sally’s journal that chronicled her courtship with Samuel Wait. Once I learned the peculiarities of Sally’s handwriting and the personalities of the characters in her life, there was nothing I loved more than sitting down at the wooden table and pulling out a stiff white folder that held the fragile remnants of my ancestor’s life. The faint musty smell of yellowed paper welcomed me into Sally’s world. I read her journal and letters over and over again until I could parse out the intention behind her words, the inside jokes, and the cryptic remarks. I followed years of story lines, looking for resolutions to church scandals and news about family members I felt I knew. I got to know Sally beyond the pious and performative portrayal she wanted readers to see in her diary. Her letters put flesh on the bones of her journal, revealing her doubts, her temper, and her wit. I had become intimate with Sally in a way I had not expected. When my friend showed me the bill of sale, I realized I had a new assignment beyond writing Sally’s story. I had to figure out how to rewrite my own.

That day in Special Collections had started like most. I emailed the staff before I came, asking them to pull the nineteenth century letters I needed to read, scan, and transcribe for my thesis on my great-great-great-great grandmother, Sarah Merriam Wait. Sally, as she was known, was the wife of Wake Forest’s first president, and while Samuel Wait’s life had been examined by various historians, Sally’s voice was silent. I wanted to change that. I enrolled in graduate school to pursue a MA in Liberal Studies and dive into the hundreds of documents written in Sally’s and Samuel’s hand. It was tedious work and by the end, I had read nearly every document that survived, including Sally’s journal that chronicled her courtship with Samuel Wait. Once I learned the peculiarities of Sally’s handwriting and the personalities of the characters in her life, there was nothing I loved more than sitting down at the wooden table and pulling out a stiff white folder that held the fragile remnants of my ancestor’s life. The faint musty smell of yellowed paper welcomed me into Sally’s world. I read her journal and letters over and over again until I could parse out the intention behind her words, the inside jokes, and the cryptic remarks. I followed years of story lines, looking for resolutions to church scandals and news about family members I felt I knew. I got to know Sally beyond the pious and performative portrayal she wanted readers to see in her diary. Her letters put flesh on the bones of her journal, revealing her doubts, her temper, and her wit. I had become intimate with Sally in a way I had not expected. When my friend showed me the bill of sale, I realized I had a new assignment beyond writing Sally’s story. I had to figure out how to rewrite my own.

The Wake Forest origin story starts with the pious ambitions of Samuel Wait and a group of Baptists determined to educate young men to spread the gospel. In the early 1830s, they scraped together enough money to buy a plantation from a North Carolina planter who had moved his operation to Tennessee. Even though it was an antebellum institution, the Wake Forest narrative included little about enslaved workers. It had been glossed over in histories, and campus lore had it that poor Baptist ministers wouldn’t have afforded to enslave people. Of course this wasn’t true. The truth had been hiding in plain sight in the archives for nearly two hundred years.

About the time that I started researching my family’s history, the university began grappling with its own. Dean of the Library Tim Pyatt, newly arrived in 2015, began questioning the Wake Forest narrative after they made plans for an online course on the history of the university. Soon, a committee was formed to better understand the Wake Forest story, which, once researched, included many examples of profiting from chattel slavery.

About the time that I started researching my family’s history, the university began grappling with its own. Dean of the Library Tim Pyatt, newly arrived in 2015, began questioning the Wake Forest narrative after they made plans for an online course on the history of the university. Soon, a committee was formed to better understand the Wake Forest story, which, once researched, included many examples of profiting from chattel slavery.

Like Wake Forest’s narrative, our family lore held that because Samuel Wait was a poor Baptist minister and Sally came from an anti-slavery Vermont family, that they must not have enslaved people. Those narratives were about exceptionalism, the idea that somehow our family and the institution that it helped to found would be different from every other Southern antebellum institution.

My first introduction to the concept of the Lost Cause–the idea in the years following the Civil War that the South could be vindicated through literature, textbooks, and iconography–was from my first graduate school class in 2016. Bill Leonard, a renowned historian of the Baptist denomination, taught our class that Southern Baptists were on the wrong side of history. His Lost Cause lecture lingered with me and called me to study more about it. I had never heard the term before, and now that I know it, I see evidence of it everywhere.

One of the things I’ve come to understand is that the iconography, art and objects that we create and venerate reflect who we are at any given time. When most of the confederate statues that we see coming down were first erected, it was at the height of the Jim Crow era when the United  Daughters of the Confederacy were trying to vindicate their slain husbands and fathers and to reassert political power for Southern whites. If our iconography reflects who we are, our narratives tell us about who we wish to be. That’s why we’ve been willing to buy into this narrative of exceptionalism, whether it’s that of my family or Wake Forest. It’s a mythology we want desperately to hold onto, one that was reinforced by the Lost Cause. Notably, one of the most powerful architects of the Lost Cause was Wake Forest alumnus Thomas Dixon, Jr. who wrote The Clansman in 1905 which was made into the movie Birth of a Nation in 1915. Dixon was heralded as one of our most honored alumni for many years. Most historians agree that these works were responsible for the rebirth of the Klan in the early twentieth century. The Lost Cause narrative seeped into every aspect of our lives in the South, and therefore Wake Forest. This narrative also created the myth that the Civil War was fought for “states rights,” and not slavery, which was taught to me at Wake Forest in the early 80s. So it’s not at all surprising that both my family narrative and the Wake Forest narrative were recast in a romanticized light that glossed over the sins of slavery.

Daughters of the Confederacy were trying to vindicate their slain husbands and fathers and to reassert political power for Southern whites. If our iconography reflects who we are, our narratives tell us about who we wish to be. That’s why we’ve been willing to buy into this narrative of exceptionalism, whether it’s that of my family or Wake Forest. It’s a mythology we want desperately to hold onto, one that was reinforced by the Lost Cause. Notably, one of the most powerful architects of the Lost Cause was Wake Forest alumnus Thomas Dixon, Jr. who wrote The Clansman in 1905 which was made into the movie Birth of a Nation in 1915. Dixon was heralded as one of our most honored alumni for many years. Most historians agree that these works were responsible for the rebirth of the Klan in the early twentieth century. The Lost Cause narrative seeped into every aspect of our lives in the South, and therefore Wake Forest. This narrative also created the myth that the Civil War was fought for “states rights,” and not slavery, which was taught to me at Wake Forest in the early 80s. So it’s not at all surprising that both my family narrative and the Wake Forest narrative were recast in a romanticized light that glossed over the sins of slavery.

It’s been a long journey for me personally and professionally as I navigate these newly revealed truths and try to understand how they’ve shaped the person I am, and the institution Wake Forest is. It’s important to know this and to share these stories. We have to admit that the exceptionalism my family thought it had is like the exceptionalism Wake Forest thought of itself. The truth is that our story is not unusual for a Southern institution and we need to be honest about that. Author Brene Brown writes that you either walk inside your story and own it or you stand outside your story and hustle for your worthiness. I’m ready to walk inside mine.

If you are interested in learning more, read my essay and others in Wake Forest’s Slavery Race and Memory Project’s recently released publication To Stand With and For Humanity.