What if the Hokey Pokey Really Is What It’s All About?

I’ve performed the hokey pokey in about half a dozen countries, with Mongolian guides in the Gobi desert and indigenous people in the high Andean mountains. While the locals don’t know the words, there seems to be a universal language in the connections we make when we “shake it all about.”

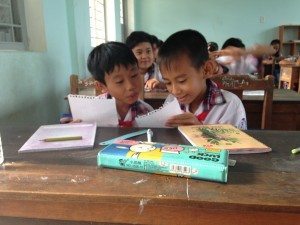

Recently, the hokey pokey made another international run, this time in a school yard in rural Vietnam. About 20 5th graders who spoke little English followed the cues of a handful of Americans to offer various body parts to the circle and turn themselves about. They giggled and danced and clapped as they mimicked our moves.

I was in Vietnam on a two-week service trip with ten students from Wake Forest University. We were there to volunteer alongside our Vietnam YMCA hosts who do great work throughout the country.

I’ve read plenty of commentary questioning the value of global service trips. Some articles question the motivation behind “voluntourism,” as it has come to be known. Some suggest that people wear it as a badge of do-gooder honor. Others warn that global service perpetuates the “white savior industry” or, in some cases, that it actually creates as many problems as it solves.

I joined the journey with a few of my own questions. On the one hand, this trip would be a living example of the practice of Pro Humanitate, our university’s motto meaning “for humanity.” These students had signed up with an ardent belief that they would make a difference in some way.

On the other hand, we would only be there two weeks. Could we really make a difference in that time? Yes, we would teach English to a handful of students. Yes, we’d pour concrete, grout floors and paint the walls of a tiny schoolhouse. But how much difference would we make? You can’t teach a child English in a few short days. And couldn’t the locals build the school just as easily if we had sent them cash?

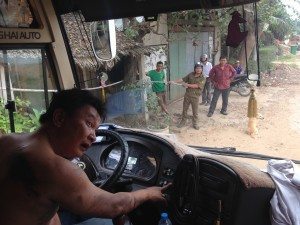

Following a few days of orientation in Ho Chi Minh City, we departed for a week of service. After navigating the narrow, dusty roads of the Ben Tre province in the Mekong Delta, the bus driver deposited us at an elementary school, where we were ushered into a small room adjacent to the principal’s office.

Over biscuits and cups of tea, the principal’s welcoming remarks were translated for us.

He talked about the poverty in the region, which led to meager school resources. Our gift of laying concrete and applying grout would indeed make an impact, he told us, as we’d be transforming an old school house into a usable space.

The rural area limited their ability to attract teachers who spoke English, making it nearly impossible to match the English classes the children’s more urban counterparts enjoy. He was no Pollyanna—he knew we wouldn’t teach his students English in six days. But he did know how we might make a difference in their lives.

“I simply ask that you teach with your heart,” he said. “Make them feel that studying another language is fun and get them excited about learning more in the future.”

Teaching English that day was a little like the hokey pokey, creating a moment that transcended global differences and inspired everyone involved—the teachers and the students—to view the world through a lens of connection and possibility.

In his book The Cathedral Within, Share our Strength founder Bill Shore writes about the work of Gregg Petersmeyer, who has spent much of his career trying to better understand the human motivation behind social activism.

“Through his research, a variety of factors contributing to community activism were identified, including one Petersmeyer called ‘the random triggering event…’ a catalytic, perhaps dramatic, occurrence that seemed to push them across the line from concerned to committed,” Shore writes.

That led Petersmeyer to ask another question: how can we make such events nonrandom? If we can predict and create the conditions that generate them, will that result in more engaged citizens?

Shore points out: “The question…is a fascinating one, and its pursuit reveals that the triggering factor is not an external event so much as an internal event. It’s not about something you see happen in the world, but rather about a strength you see inside yourself…learning something new about your own unique ability to contribute to its solution. “

With the right community partner, international service can eliminate the randomness of the triggering moment, creating a fertile ground for an exchange of hope and possibility. At its best, it blurs the lines between server and served.

As the days went by, I watched the participants closely—the Wake Forest students, our young YMCA hosts, and the children at the school.

The travelers tapped into endless strength as they hauled countless bags of concrete and labored over lesson plans.

Our hosts recognized their ability to span continents with their patient and good-humored guidance.

The young children seemed to surprise themselves with their capacity to learn a new language.

Like the slow trickle of the Vietnamese coffee dripping into my sweet condensed milk every morning, day by day and moment by moment, I saw young people on both sides of service begin to wear the face of possibility—in themselves and in the world.

Maybe that really is what it’s all about.